Slappin’ Glass sits down this week for a second time on the show with one of the world’s most sought after high performance coaches, Dr. Gio Valiante! In Round 2 the trio dive deep into the areas of fear and anxiety in high performance, finding flow states, and attributions of success and failures.

Transcript

Dr. Gio Valiante 00:00

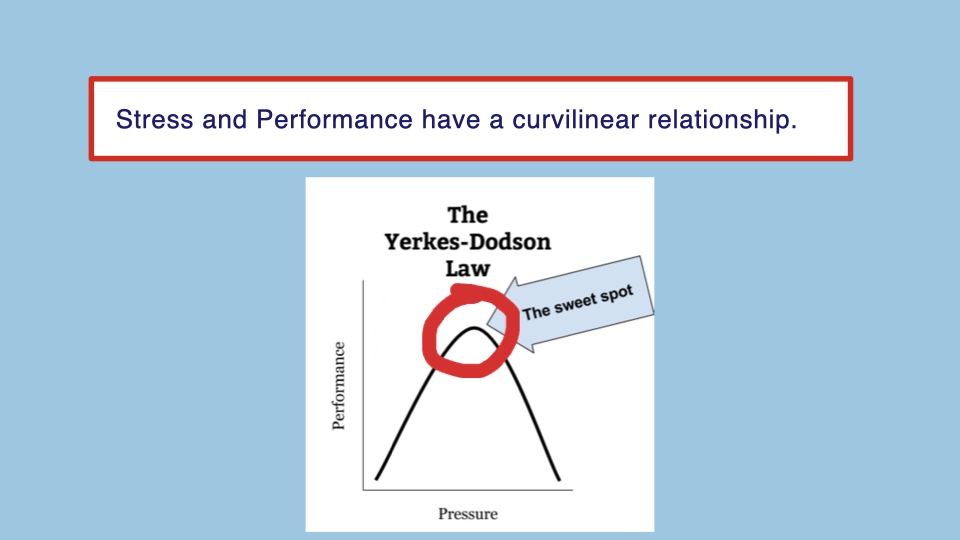

As stress and pressure increases, it tends to elevate the skill, right? So pressure increases, well, player rises to the occasion. But then what happens is at a certain point, it’s a curvilinear relationship. As pressure increases, skills go down.

Fear can be a great thing to do. People are playing for survival. It gets all your resources. And all of a sudden, skills tend to go down. So to try to find what’s called the zone of possible development, what’s that optimal level where you’re training your players, where all their senses are fully alive, where they’re going as hard as they can, deep engagement. Underneath that, there’s also you’re building the confidence and you’re showing them, hey, look what you’re becoming capable of. So you’re challenging the players. They’re getting better at playing under pressure. You’re showing them that they’re getting better under pressure so that the next day, you can challenge them at an ever higher level.

Dan 00:57

Hi I’m Dan Krikorian and welcome to Slappin’ Glass. Exploring basketball’s best ideas strategies and coaches from around the world. Today we kick off the new year by welcoming back to the show for a second time Dr. Gio Valianti. Dr. Gio is one of the world’s most sought-after performance coaches and his first conversation with us is still one of the most popular of all time.

In this special episode we dive deep into the topics of fear and anxiety and performance, the psychology of flow states, attributions of success and failures, and much much more. On top of this conversation Dr. Gio has also graciously provided us presentation slides and extra material about these topics which you can learn more about in our Sunday morning newsletter.

For more information on Huddle Instat visit huddle.com slash Slapping Glass today. And now please enjoy our conversation with Dr. Gio Valianti.

Dan 02:23

Dr. Gio thank you so much for making the time for coming back. The first episode was one of our most popular of all time. Coaches loved it and we thought you know we got to dive in for more and so thank you very much for making the time today for us.

Dr. Gio Valiante 02:43

Thanks for having me Dan, super excited to be here. I love the time we spent together.

I also got some emails from coaches around the country. I like to teach I’m a teacher college professor for 15 years. So I just like to disseminate knowledge and the fact that it landed with people is exciting for me. So thanks for having me back.

Dan 03:02

Absolutely. Today what we wanted to start with, and we’re going to kind of hit some major themes in your world and things that relate obviously to ours and high performance and all of that. And the first one is fear and anxiety. And I think the jumping off question for you is what role does fear and anxiety play in performance?

Dr. Gio Valiante 03:25

If it’s okay, I’ll backtrack a little bit. When I was a young graduate student at Emory University, and I started doing research, the vehicle I started using to explore psychology at the time was golf. And mind you, this is going back to the early nineties. When sports psychology, there were maybe two programs of sports psychology at universities in the country. So sports psychology wasn’t really a real thing, but I was in a psychology program, always interested in sports. So I just started doing a little study and I was using golfers as sort of the participants in my study to try to understand how athletes in general, particularly at the time golfers experienced the psychology of their sport. And what happened was in all these interviews, I was interviewing PGA Tour golfers as well as recreational golfers and competitive amateurs. And one of the remarkable things that emerged just naturally out of the dialogue was this idea of fear. And nowadays everyone talks about fear, but at the time it was a really misunderstood thing. And oh, by the way, at the time, there was debate in psychology whether science could actually understand emotion.

So mind you at the time, the field of scientific psychology wasn’t even a researching emotion because they thought there’s no way to empirically measuring motion. It wasn’t until neuroscience and the study of the brain itself that we started to dive into the area of emotions. The convergence of neuroscience and the study of emotion converged with my study. And what happened over the course of 120 interviews is the recurring theme of fear started to emerge. And of course, it begged the question, why are people afraid playing the game of golf? You know, at the time, like Lawrence Taylor as a linebacker in the NFL, Bill Laimbeer in the NBA, it’s like, you’re not gonna get tackled. You’re not gonna get punched by Mike Tyson. How could you be afraid playing a game where there’s no threat to your existence? And yet it was the dominant theme that came out so much so that the first book I wrote ended up being called Fearless Golf. So this book that I wrote was supposed to be just for a very small sample of elite golfers, but the theme of fear in Fearless Golf struck the chord with so many people that the book ended up becoming sort of a bit of a global phenomenon of seven languages, surprising everybody, including the publisher.

And I say this to you just to catch us up to speed because fear is one of the things that we in psychology call one of the universalities of the human condition, right? That there are certain features of being a human being that are common to all of us. That means it’s independent of gender, of geography, people in Russia, in China, in South America, in Australia, like the things that are universal to human beings across the entire spectrum of humanity, the universalities. Going back to this idea of fears, the fact of the matter is it’s something that’s universal to the human condition, right? Everyone has a relationship with fear. Now, what’s interesting about it, and that we’ve learned over the last 20 years, so the fact that it’s universal is interesting.

Dr. Gio Valiante 06:19

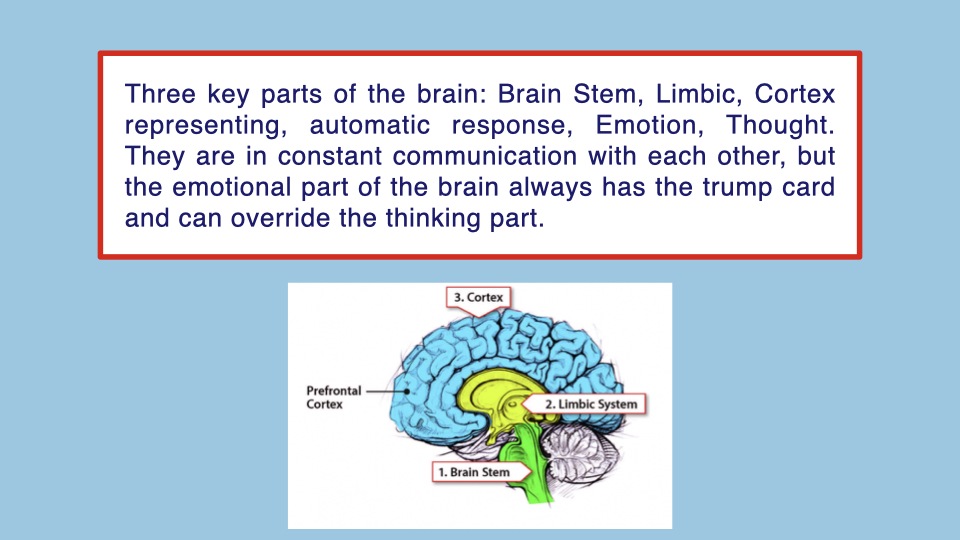

The other feature about fear is that if you study the architecture of the brain, it’s just a quick, simple understanding of the brain. There’s three main parts of the brain. There’s the brainstem, and the brainstem is the thing that we share and come with all animals, including reptiles. The brainstem, it’s the oldest part of the brain. It regulates our heartbeat. It regulates sort of human functioning. It’s things we don’t really think about, central nervous system. Then what happens is as the brain evolved, the next level was sort of the emotions that human beings have.

We share like rats, why they do studies in labs with rats and various things, and sort of the limbic system, which features all the emotions, and then the cortex, right? Which we do all our thinking. So here’s interesting, talking about fear in sports, is there’s a never-ending interaction between the limbic system, which houses our emotions, including fear, and the cortex, which is where we do all our thinking. And so there’s this constant communication, but what is known is that our emotional system, predominantly fear, is more powerful than our cortex.

In other words, to quote Henry David Thoreau, he said, the heart has reasons the head can never understand. Now to translate that, really what we’re talking about is our emotional brain is far more powerful than our cognitive brain. And that’s true even in modern times. What you’ve seen in modern day was sort of analytics and sort of sports has become more cerebral. So categorically across all sports, particularly at the elite levels, athletes have to think more. No longer can you get by in pure athleticism. But what that’s done is it’s tricked people into thinking that emotions, particularly fear, no longer play a role in sports. In fact, it plays more of a role than ever before, and I’ll explain to you why.

So if you look at the circuitry of the brain, the way to think about fear is there’s a little almond shaped part of the brain. I don’t wanna be too theoretical because I know this is for practitioners and coaches and players. So let me get to the past value of the idea. There’s a part of everyone’s brains called the amygdala. It’s about the shape and size of an almond. And what happens is as we are receiving information through our senses, information comes in one of two ways, called the high road or the low road. The high road is when information goes to our cortex and we start thinking about danger or threat. But before we can think, it’s actually already processed into our emotional brain. So we feel fear before we can actually think about the thing that causes us to be afraid.

So let me tell you what happens with coaches. Very often as a player or as a coach, trying to coach a player, you’ll see that a player is playing scared and you can ask the player, what are you afraid of? They can give you all sorts of answers, but the reality is when we are afraid, very seldom do we actually know what we’re afraid of.

Dr. Gio Valiante 09:07

So what happens is the feeling comes first. And then the way the brain works is we try to find someone, we find a home for that fear. So we’re afraid. And then we start trying to find the thing that we’re afraid of, same with anger. I’m angry and I’m gonna find the closest thing I’m angry at my coach or my player or my parents or what happened last week or the media, someone criticized me. So the takeaway is that emotion happens before cognition.

The way the brain works, this is really important for coaches to know because you have to understand that you’re not only coaching skill, you’re coaching the emotional life of a player. And in fact, we talk about modern day coaching. I think we’re coaching has evolved. And I think this is a really good way is that you understand that you’re having to coach the total player, the total individual. It’s not just about skill development. It’s not just about toughness. The toughness is part of it is that you’re coaching the emotional life of a player, really important, right?

And so the circuitry in the brain, the way that we’ve evolved as humans is there’s twice as much dedicated circuitry going up as opposed to coming down, meaning our fear circuitry is like a fire alarm. It’s like a throw switch. So if I pull a fire alarm in a building, what will happen is a series of events will happen. Number one, the electricity turns off. Number two, sprinklers come on. Number three, it sends a signal to the fire department. Number four, alarms go off, but these things happen automatically without any intervention. The same is true of the brain. Once an athlete starts to play scared, there’s a sequence of events that happen automatically.

So the first thing that happens is perception shifts. In other words, the size of the basket, you have to understand there’s an inverse relationship between confidence and anxiety and fear, right? So we lose confidence, confidence goes down, fear and anxiety go up. Once that happens, once the amygdala gets invited to the table to react, first thing that happens is our pupils dilate. So there’s a perceptual shift. So basketball, the hoop starts to look smaller. Passing lanes look more narrow, threat grows. So whereas when we’re confident, all you see is opportunity. All you see is passing lane. All you see is lanes that you can drive. The different ways you can score, you can’t even count them. But all of a sudden in the same setup, the same offense or defensive schemes, when you start playing scared, you don’t see those opportunities because perception shifts. The hoop looks small. The player who is open doesn’t look open. So all of a sudden, if you’re a guard or if you’re on the wheel, you don’t see the opportunities there. Perception shifts, blood pressure increases, heart rate goes up. What’s interesting here now is if you look at my hands, see the capillaries, see the pinkness in my hands? Those are blood vessels, those are capillaries. That’s what gives me feel. And I have those blood vessels throughout my entire body.

Dr. Gio Valiante 11:57

Just like with the fire alarm, as the sequence of events fall, once the amygdala triggers the fear response, after that perception shifts and the hoop looks small and the passing lanes are no longer there, we start losing blood in our hands and our forearms. All of a sudden, we no longer have feel. So what you’ll often see, for example, out of a tennis player, a tennis player who’s playing scared, they’ll grip the racket tighter. And so the same motion all of a sudden, instead of being able to play to the baseline, they hit to the short court. That’s why they get killed.

Basketball players, where you see is, like they start short arming shots. They don’t finish their shot, right? And it’s not a skill thing. So what happens is coaches focus on the skill itself. The skill is there, but the fear response makes it impossible to finish the skill that we have, whether it’s extension or release or what happened, right?

So perception shifts. Where we used to see opportunity, now we see threat. Capillaries constrict, we lose our feel. We lose our fluidity of motion. We lose our rhythm. Third thing that happens is there’s, so you have to understand what happens is, and we’re gonna talk about flow states in a minute. One of the characteristics of a flow state, when you talk to athletes in flow or in the zone, is they’ll often report that it feels like things are happening in slow motion. And they can anticipate two or three moves ahead, because that’s what confidence and flow does. We can anticipate what’s gonna happen. We’re in control, we’re in command and time, even though we’re moving quickly, we don’t feel rushed. Well, the opposite happens when we’re in a state of fear. When an athlete’s in a state of fear, they often feel rushed, right? So all of a sudden they’re rushing, but they’re not moving quick, they’re just thinking quick. So perception shifts, they’re going through a physiological change in their body, and all of a sudden time starts speeding up on them, and they start making dumb mistakes.

And then the fourth thing that happens, this is really probably the most important that nobody pays attention to, is reactions change. So think about it this way. If you have a player that you’re coaching, and that player is on a run, he’s been playing beautifully, having a great start to the season, or even forget a player, talk about the whole team. You have a team that’s playing with confidence, and somebody makes a mistake. What is the typical reaction to a mistake if a player or team is playing with confidence?

Pat 14:09

they’re playing with confidence, then I think they can, would they be able to ignore it and just be resilient, bounce back? Like they have the last, like you said in this example, five, six games of success that they’re going to lean on rather than the one, two bad possessions.

Dr. Gio Valiante 14:23

That’s exactly right. So one of the things we know is that confidence acts as like a buffer. It’s like it becomes Teflon. So what the brain does, it’s like, I made a couple of mistakes. That’s ok. I’ve made mistakes before, and we’ve won. Or I’ve made mistakes before, and I’ve rebounded. No big deal. So what happens is that perceptual shift, the fear response does not get triggered. When you’re playing with confidence, you can make a lot of mistakes and absorb them and keep your composure.

The opposite happens for a player or a team who are in a state of fear or panic. They react to mistakes differently. If you think about just the cause and effect, why do we react with fear? Why does a human being start doing anything with fear? The typical reason is the brain is anticipating pain. So think about it this way. If I’m a player, I miss a shot in practice, I’m doing a drill, and someone comes up to me, and they deliver some version of pain. And that pain could be in the form of physical pain. So let’s do an experiment. I don’t want to bring abuse into place. We’ll just do a theoretical experiment. Player misses a shot. I take one of those electric buzzers, like we had as kids, those little things, a little bit of an electric shock. And I put it on. It just gives you a little jolt of electricity. Oh, what are you doing? Well, I’m trying to teach you not to miss or not to make a bad pass or not to do something stupid. So practice continues. Player does something stupid. But I come in, and I deliver that shock of electricity just a little bit of pain. They feel that shock. They’re like, man, what is that? As a coach, you’re saying, well, I’m trying to teach you not to do dumb things. You do dumb things here, and that pain is coming. So here’s what happens now in the brain. Now the brain of that player is saying, if I mess up, pain is coming. So now I start playing scared. Because why is that? The brain is simply designed to learn. It’s a learning mechanism. And what it’s learning is mistakes are not OK around here. When I make a mistake, pain is going to come.

Now the brain starts doing its job. It starts flooding. You start playing scared. It’s not because the brain isn’t working. Your brain is doing what it’s designed to do is learn from past experiences. What’s also interesting is we know is that psychological pain hurts more than physical pain. What’s the worst kind of psychological pain a human being can feel? One of the worst is humiliation and embarrassment. So now let me connect the dots. A player’s out there, or a team, and they’re playing bad. And because they’re playing badly, instead of reacting with acceptance or composure, they start going down that downward spiral where it’s embarrassing. They’re being laughed at. They’re being humiliated. Maybe they’re families in the crowd, or they’re friends, or a team. Your coach embarrasses you in front of your teammates. What happens sequentially is the next practice or the next game, the brain starts thinking, oh, man, the last time I was in this situation, pain came.

Dr. Gio Valiante 17:16

I was embarrassed. Coach made me feel embarrassed or fanned.

And the brain starts free reacting, and now you’re playing scared. And what we know is it’s easier to lose confidence than gain it because the fear circuitry in the brain is so powerful because it’s designed just to keep you alive for survival. What you’ve seen over the years, I imagine, as coaches, here’s what the psychological research shows. It’s far harder to build confidence than to lose it. And once someone has lost confidence, starts playing scared, good luck. Good luck for covering a player who starts playing scared. And that’s because it becomes an automatic reaction, automatic response. The two things we know, the game of basketball attacks in elite players are confidence and motivation. And so, again, we talk about confidence. As confidence goes up, fear goes down. But as we lose confidence, we start playing more scared. And fear is so corrosive. What it does is it distorts our ability to see reality as it is. The fear response distorts our ability to see reality as it is. We misinterpret what a coach may be saying. We don’t read the floor very well. As situational operators on the floor, you start playing scared. You stop taking risks. You stop making plays happen. And it’s that downward spiral. So the takeaway here that I would say to all coaches, yeah, you have to hold players accountable. Yeah, you have to build great resilience. You have to be very, very mindful to never introduce humiliation or embarrassment into a player’s life because the brain is more scared of being embarrassed than anything. And if a player thinks that if he fails or she fails, then you’re gonna make them feel embarrassed. That’s the very thing that triggers the fear response that will undermine whatever skills or abilities that you’ve worked so hard to cultivate.

Pat 19:11

Is it as a coach more about than trying to have players play without fear or quiet the fear when it starts to happen?

Dr. Gio Valiante 19:19

The answer is both, right? So one of the things you’ll often see that we’ve seen historically, and this is a really, I think a really interesting phenomenon, you see in the NFL, I see in the NBA, you see really in a lot of sports, is players who seem arrogant, right? This is sort of the never-ending story of a player who hypes himself up or surrounds himself with people or constantly hyping him up and telling him how great he is, and sometimes it goes too far so the player almost becomes uncoachable, right? Now, it begs the question, why does that happen? Why has a player evolved to the point where he’s acting or demonstrating such arrogance? Here’s why. If in fact confidence is the buffer to fear, is the thing that protects us from fear, players have adapted to learn, I have to do anything I can to protect my confidence. Even if it means being arrogant, even if it means surrounding myself by people, we’re going to constantly tell me how good I am. Even if it means my coach is criticizing me, I’m going to shut him out. Even if it means I’m going to shut out the media. In other words, it becomes an adaptive mechanism because they’ve learned at some point, I can’t play this game without confidence. And so even if I have to go over correct to arrogance, the reason they’re doing is to protect that confidence.

Now, it begs the question, what do you do with that situation? As a coach, you have to find a way that’s twofold. Number one, you have to let all players understand, and this is the hardest thing in modern times, is because social media is so prevalent. Fame equals dollars. Sports has become such a public thing. The number one thing that people are afraid of, that players are afraid of, is being judged socially, right? It’s being criticized, being embarrassed in front of large numbers of people and or their family and or their teammates. So you have to create a culture and environment and teach them your confidence cannot come from the outside, from externalities. That’s not the source of your confidence. Because if you’re confident, the source of your confidence is approval from other people, then you’re also giving other people the power to take away that confidence. And when you start playing badly, which you will eventually, that’s why you start playing scared. So you have to ground your confidence and root your confidence in something more substantive than other people’s perceptions of you.

Now, why is that? Because social judgment in the form of praise or criticism is the number one source of fear in the human condition. It makes sense. If you think of human evolution, to be part of a community or part of a tribe meant survival. To be alone, to be isolated with certain death. So to be accepted by a community meant survival. Well, those are very old parts of the brain that still react that same way. In other words, the brain didn’t evolve for you to be a competitive basketball player.

Dr. Gio Valiante 22:18

We still have these relic parts of the brain that react in modern times, the way that they have for thousands of years. And the main driver that is social acceptance. So as a coach, it’s this balance between unconditional love, unconditional support, but balanced with, I’m going to make it hard on you because I care about you. I’m going to work you as hard as I can to develop your skills, but it’s coming from a place of love and support.

And oh, by the way, confidence is going to come from in this room, in the team room, from within the team, right? Or from within yourself. Actually, this is the key question. I think if you want to understand the psychology of fear, if you walk the dominoes back, the fundamental question is why do you play basketball? If a person is playing basketball because they want to prove something to someone else, or they want the approval of a coach or the approval of someone in their community, that’s immediately inviting embarrassment as a reaction. You can never play the game for the approval of other people. Because if that’s why you’re doing it, that’s opened you up to the sensitivity of criticism, embarrassment. And that I would say 100% of the time that I’ve seen a player, I work with people who do investing and professional investing in the stock market. One of the common sayings they say in the stock market for traders is, hey, if you want to feel loved by a dog, because you’re not going to get it here. And it’s similar with basketball at the highest levels. If you think that as a human being, you’re trying to solve for feeling loved, you’re not going to get that out of the game. You can love the game and your teammates can love you, but the fans and the media will never give that to you. And if in fact, that’s what you’re trying to solve for, you have to find that somewhere else so you can play fearlessly.

Dan 24:00

Dr. Gio, within all this, I think about stress and like we’re talking about fear and some deep-seated things, emotional stuff, but then when it comes to like putting stress on players because the game is going to be stressful, there’s a time, there’s score, there’s fans, all that kind of stuff, what coaches can do to basically get a healthy response from stress so that you have a team that is ready to take on everything that happens in a game from everything from training, from practice, from how you talk to them so that it’s healthy stress, it’s good stress and it’s not leading to fearful things like we’ve talked about.

Dr. Gio Valiante 24:38

And so to answer the question that Pat asked earlier, is the goal to not invite fear into play or to teach players what to do when that threat comes? And it’s clearly the latter, to develop resilience.

Resilience and confidence are the Teflon to protect people from fear. And I know you know this as coaches, but I’ll sort of validate it that psychological research shows it, in fact, it’s how you practice. You have to practice in hard conditions, because what happens is the brain habituates, and the brain and the body and system and the nervous system habituates and acclimates and sort of normalizes stress. So you have to create, but you have to do it in a way that’s scaffolding. You can’t just go from calm, cool to immediate stressors, right, you scaffold it and you build players into that. You can’t bring a young player who was the dominant player in high school, you know, for whom the game was easy and throw him into a tough environment, shock him and shock the system, because he’s never had those reactions. The most common phone call I get from professional athletes distributed across all sports, is the athlete for whom their development was up and to the right. In other words, they just got better and better and better. And from the age of eight, nine, 10, 11, 12, they just got better every year. And then all of a sudden they end up in a situation where they’re around all good players. So now you’re not the best anymore, you’ve never failed. And for a player who’s never failed, and they don’t know how to handle failure, and now they’re in the big leagues, it was D1 basketball, D2 basketball, God forbid the NBA. And they have no toolbox for how to handle not being the best, that’s a dangerous situation.

So the way you wanna build a resilient player is you scaffold them into those precious situations. The other thing I’ll say about that is they’re really fascinating. So we do these experiments where you measure stress and you measure performance. And what we find is this, as stress goes up, so does performance. So think of it, so let’s start. Low stress, calm, cool, almost it’s called a lazy environment, a lazy, soft environment. You have a game with players and so forth and there’s no stress. Well, their skills will likely not be deployed. All right, you increase the competitiveness, well, it’s got my attention, right? You increase it a little more. But all of a sudden, as stress and pressure increases, it tends to elevate the skill, right? So pressure increases, well, player rises to the occasion, get more stressed, right? This is the scaffolding I was talking about. But then what happens at a certain point, it’s a curvilinear relationship. As pressure increases, skills go down, right? Fear can be a great thing to do. People aren’t playing for survival. It gets all your resources. And all of a sudden, skills tend to go down. So to try to find what’s called the zone of possible development, what’s that optimal level where you’re training your players, where all their senses are fully alive, where they’re going as hard as they can, deep engagement,there’s also time for recovery. Underneath that, there’s also, you’re building the confidence and you’re showing them, hey, look what you’re becoming capable of.

So you’re challenging the players. They’re getting better at playing under pressure. You’re showing them that they’re getting better under pressure so that the next day, you can challenge them at an ever higher level. And so it becomes this never ending cycle of challenge, skill development goes up, challenge, skill goes up, challenge, skill goes up. And as a coach, you’re always finding innovative ways to keep challenging a player so it never gets stale, right? Because you want their senses to be fully alive because the reality is the way that skills develop, it’s a process called myelination. So what happens to the neural circuitry starts getting wrapped in this substance called myelin, and those are habits, those are skills. But what we know is players who are just going through the motions in like a calm, cool, easy environment, they don’t develop any skill. Just going through the motions, no one gets better. You can shoot a thousand free throws a day, but if you’re mentally checked out, you’re not getting better. And if you’re shooting fewer free throws, but you’re paying attention and you’re engaged and there’s a client, there’s a culture, and coaches setting the tone of pressure, that’s how skills development. So finding a way to build that climate where there’s pressure and those skills are being developed in that climate is the biggest favorite you can do to an elite player.

Dan 29:46

Dr. Gio, transferring to a second topic that I think flows from this first one, which is maybe the opposite of fear and playing with fear and anxiety, which is the zone, flow states. And your thoughts on how players enter, stay in, get into the flow and what that means, and I guess also what’s happening within them as well that allows them to be in those flow states.

Dr. Gio Valiante 30:12

That’s a great question, you know, flow in the zone is the holy grail of psychological research. The research on flow actually began in the 1960s from a psychologist named Abraham Maslow. And it began with a simple question. He sent out a survey in the sixties and he asked people, do you find your life thrilling? And just like in modern times, a very small percentage of people said, yeah, my life is thrilling.

So he went and found those people and started interviewing. What are you doing? Why is it? And you come to realize the people who answered yes to that were not just wealthy or famous or talented or gifted. You had mechanics, you had the factory workers, you had people in working gardens. And so what happens is this autotelic personality, people who are able to get up for any situation, you realize those are developable skills. Well, all of a sudden, you know, living life at the tail end of the curve in the highest form, it started with studies of just people living life. And of course you start to watch athletes. You’re like, oh, that’s different. So if I were to ask you, who is the basketball player that you have either watched or coached, who you’ve seen play either in the zone or in flow, you know, more than anyone else or regularly, who would you give me an example of a player?

Dan 31:23

Steph Curry.

Dr. Gio Valiante 31:23

Steph Curry, who else?

Dan 31:25

Back in the day, Kobe.

Dr. Gio Valiante 31:26

So let me ask the next question.

When you see a player in flow, what are some of the characteristics? We all know it when we see it. What is it that we see? What are some of the things that you see as a coach, as a player? What does flow look like to a coach?

Dan 31:42

I would say there’s a certain freedom of movement. There’s a certain like joy. There’s a certain just lack of fear, you know, to go on the opposite side of what we’re just talking about that you just see within them.

Dr. Gio Valiante 31:53

What else? What are the characteristics of flow?

Pat 31:55

They’re just reacting freely like in terms of how they process decisions, you know, I mean, maybe it’s also some Anticipation but I just think like they’re processing in real time everything and reacting accordingly

Dr. Gio Valiante 32:08

In fact, what they’ll have to say is I wasn’t thinking, it’s without thoughts, just reaction. You guys have ever seen this old comedy movie called, I think it was called Old School where Will Ferrell is in a debate and he’s debating and he gives this great answer and he’s like, ooh, what just happened? I blacked out. Yeah.

Pat 32:26

Haha

Dr. Gio Valiante 32:27

There is a baseball movie called For the Love of the Game where the pitcher gets in the flow and it captures it. It’s really great seeing the way they use film to capture what it’s like for an athlete to be in a flow.

So let’s talk about flow for a minute. Some of the characteristics of flow. Number one is we call the paradox of time. So when we interview athletes after they’ve been in flow, because you can’t interview them while they’re in it because that would get them out of it. One of the things that psychologists do is right after a great game or a great round of golf or a great match is, hey, look like you’re in the zone out here. Tell me what just happened. Describe that for me. And what you’ll see is a few things. Number one, the paradox of time. And here’s what I mean by the paradox of time. Athletes in flow say that it felt like time was moving very slowly, but in retrospect it went by very quickly. It’s like, oh my God, it’s over? I didn’t even notice it. Now the opposite’s true when a player’s not in flow. They feel very, very rushed. It feels like things are taking forever, right?

So the paradox of time, the paradox of effort is the second paradox of a flow state, meaning the anticipation that this is gonna be a really, really hard game, this is a great team, is against the fact that it felt effortless while I was out there. So the anticipation of challenge is one of the triggers of flow, which is why, for example, if you underestimate opponent, let’s say you have the better team, but you underestimate your opponent, very often you play down to the level of your opponent. But why is that? Because one of the things that triggers flow state is, that’s why, by the way, just as an aside, the underdog mentality is the best, if you could find a way, no matter how good your team is, to go through every day with an underdog mentality is the best thing you can do for a player.

Why? Because what we call the golden rule of flow, it’s called the CS relationship, challenge versus skill. So one of the triggers to flow is to make sure that if your team is playing at this level, you have to challenge them here. They’re playing at this level, challenge them here. And that’s what the underdog mentality does. It’s this relationship between challenge and skill. World records are never broken in practice. Your players are never gonna elevate when there’s nothing on the line. In fact, just today, Roger Federer put out a tweet thanking Rafael Nadal. Rafael Nadal’s about to retire. In that tweet that Federer put out, he talked about, hey, you made me a better player. You forced me to evolve my game, right? Nadal was here, Federer was here, especially on play. So Federer had to elevate his game. Some of the best matches he ever played were against the better opponent. If I’m great at tennis and I’m playing against someone who stinks, that’s not gonna trigger a flow state.

Dr. Gio Valiante 35:05

Now, the thing about flow is it doesn’t have to be the actual challenge, it’s perceived challenge. So what you can do as a coach is you can frame the game in so many different ways, even if you’re playing against a worse team, you can frame the game as a way to make sure that your players are playing for their lives, right? And you always have to do that.

So going back to what we’re talking about, the paradoxes of flow, paradox of time. Feels like time is moving slowly, but in retrospect, boy, that happened quick, I can’t believe it’s over. The paradox of effort, the anticipation that this is the most important game I’ll ever play in my life. This is gonna be the hardest challenge I’ve ever faced, juxtaposes with the fact that I was, flow states tend to be effortless. The paradox of awareness. So what players didn’t flow often reports like, yeah, everything was happening in slow motion, but like, I was aware of everything that was happening on the court. I knew where every player was, whether they were behind me or in front of me, I could see the marks on the ball. I noticed everything that was happening on the court. It’s almost like this transcendence state of mind where you’re hyper aware. Now, juxtapose out the fact, it’s like, oh, well, did you notice that LeBron was watching? I didn’t notice that. Did you notice it was a full arena? No. So while they’re hyper-focused of everything that’s relevant to the game itself or to their job, they block out some really, really obvious things. Now, why is that? Players in flow, the brain has a way to filter out anything that’s non-essential and dial in on only the things that matter with hyper-focus. Did you hear me yelling at you? No, coach, I didn’t even know you were talking at the time. And so this paradox of awareness, which is a paradox of time, while you’re playing, everything slows down, but it goes quite quick.

Paradox of effort, most states end up being effortless. Paradox of awareness. which is you’re hyper aware, everything that’s important, the things that coach has been teaching since you were eight years old. All the coaches say, focus on your own game. Don’t worry about this. You’re actually able to do those things. And so the brain is filtering out all your training to that moment. And you’re elevated. Right. And so the fourth characteristic of flows was called the paradox of control. And this is probably the most fascinating part of it. So going back to we talked about fear. One of the other characteristics of fear is you’re afraid of losing control. You’re trying to control everything, right? And you’re thinking about your mechanics. You’re thinking about you’re trying too hard, right? When you’re scared, you’re trying too hard. And you’re overthinking. And so your rational brain is interrupting the habits that you’ve done. You’re overthinking. One of the things that happens in flow states, we call the paradox of control, is you gain control by giving up control. So when you see a player who’s playing scared, they’re trying to over control the game or over control things.

Dr. Gio Valiante 38:00

What you’re actually trying to cultivate in players is called psychological freedom. What you’ll often see is spontaneity or just being reactive or being creative in the moment, right? Because creativity is another aspect of the state. So the paradox of control is you gain control by giving up control. We see this in tennis and golf a lot. What you’ll often see coaches on a PGA Tour or ATP doing is like, hey, man, let it go. Hey, free it up. Psychological freedom, playing with freedom. And what they’re trying to do there is get players to knock over control what’s happening. And so that spontaneity, that freedom, that creativity.

In basketball, when you see a team that’s playing with freedom and peaking in the earlier and middle part of the season, what you see also is creativity. Now, what’s important to this paradox of control? Going back to what we said earlier, the only way that a team is able to play with freedom and creativity because they’re taking risks is if they know that they can take those risks without punishment, that they can take those risks without being embarrassed, that they can take those risks and we don’t pull it off. Because again, as a coach, you don’t want to put any artificial seal. You want your players to elevate. You want them to peak later in the season likely. The only way to do that is to give them the freedom to take risks.

But if you’re going to pound your players and hammer them every time they make a mistake, they’re not going to take any risks. If they don’t take any risks, there’s no flow. And that’s why what you’ll often see is great coaches can take a team and get them to play above their resume or above their recruiting numbers, right? Great coaches, whatever you give them. Now, why is that? They can elevate players because they’re giving them permission to be creative. Now, when we talk about mistakes, I’m not advocating that a coach that’s ok to make mistakes and I’m not going to punish my players. We call the quality of a mistake that a player makes, right? So there’s mistakes and there’s mistakes. I’m not going to forgive mistakes that if you’re repeating the same mistake over and over again, I’m not going to forgive a mistake that’s just something we’d coached out of you, but you’re doing anyway. I’m not going to forgive a mistake of selfishness if you’re supposed to be the guy, team player, distributing the ball. But there’s things I am going to forgive. Hey, you’re trying to innovate, to elevate, to do something cool.

You’ve got to find that beautiful balance between discipline and structure and creativity and freedom. So the fundamental question is, if you’re coaching players and the ideal is to get your player or your team to play in the state of flow, how should you think about that? OK, well, here’s how you think about it. Flow happens in these cycles we call peak performance, right? You call it peak performance for a reason. Peak performance is not a straight line. Otherwise, there’s no peak.

Dr. Gio Valiante 40:42

Now, you can try to get your team to play at a certain level, at a high level, consistently. But the reality, even in that high level, what you’re going to see throughout a season is this. So as a coach, if you start trying to press too high of a level too frequently, what you’re going to do is burn your team out and exhaust them.

Why? Because a game attacks confidence and motivation. If you exhaust your team, you’re going to lose that motivation, which is required for flow. One of the characteristics we know about flow, guys, is that after a flow state, people are exhausted. So when you’re in flow, you have boundless energy, right? You have so much energy. You’re sprinting up and down the court. You’re jumping higher than ever. It’s like it’s effortless. Juxtapose that with after flow, you’re exhausted. And so as a coach, you have to understand the cycles in sports like swimming and track and field. They call it periodization, where you’re trying to get your people to peak, and then you’re actually guiding them down. The same is true in sports like basketball, football, golf, is you want to guide your team, your players, so their peak energy, their peak focus, their peak motivation. But you also better plan to let that come down and decompress so you can build that cycle up again for the next peak and come down. It’s a mistake as a coach. If you see your players after a great run, you start seeing them come down and start getting a little sloppy, the answer is typically not to scream at them and push them harder. The answer is typically to actually give them a couple of days off or just let them decompress, come together as, you know, I think Buffalo does a great job of this. If you listen to the players on the Buffalo Bills right now, they talk about, hey, after practice, we hang. There’s a community that’s that high, where they’re anticipating each other. But there’s also decompression and humor and psychological freedom. And that’s what you’re trying to create in a team. The only way to do that is to create these conditions for flow where your team can peak or your players can peak. Then you have to give them a way to come down so they can build up for the next peak level of flow state.

Pat 42:40

You hit a lot on how coaches can, in my mind, like on the macro level, think about the environments, the training, but what’s also interesting, if you look on a game and say in the first half, your team is in this flow or a player and they’re at a peak state, but then halftime hits, how would you help a coach think about knowing these paradoxes to keep your team playing in that flow after a natural disruption in the game?

Dr. Gio Valiante 43:05

That’s an unbelievably good question, Pat, and it’s the kind of question that only a coach or a player would ask. One of the things we know about flow states is they have a window of time. When we think about flow, we can’t create it. There’s no way to actually create it automatically.

What you do is you can almost think of the metaphor of these cuckoo clocks in Oklahoma who go chase tornadoes, these nut jobs. So what they’ll do is they go to a place like often into Oklahoma or Texas, and they’re looking at these screens. And what they’re looking for is temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, seasonality. So look at all these variables, and they know if these things line up, there’s a good chance. There’s a higher probability you’re going to get a tornado, same with flow. You’re trying to create the conditions for flow. The conditions for flow are high motivation, high hunger, high energy, challenge. There’s a challenge in front of them. They’re getting feedback on the challenge. Basketball is a game of immediate feedback. If you see that a player has cycled through, they were in flow, and then it’s over. All of a sudden, you can literally see focus comes down. The fluidity of their movement becomes a little more clumsy. They’re not as decisive. They’re thinking. You do a couple of things. Number one, you can scheme around that in a particular player, scheme around that. Number two, replace the player. Here’s one of the biggest problems in basketball. I mentioned this to you guys in the last podcast, and I’ll mention it again. And I know basketball is going to solve for this because it’s an innovative game like every other game. Players care too much about minutes. They care more about minutes than they do about peak performance. And the best thing you can do for a player who’s out of flow is get them out of the game and let them rest because that’s going to give them a chance to sort of decompress, and then all of a sudden, you can catch.

If you want to put them in the fourth quarter and give them some resting minutes, they can sort of cycle back up into it. Or what’ll happen is you give another player a chance who is hungry, who’s got that motivation, who’s trying to earn spots on the floor. That requires that players trust their coaches a lot, but the reality is there’s no way to force flow. And so if you see that a team wasn’t flow, now what you never want to do, we talked about the psychological equivalent of the prevent defense in football. In football, it’s okay, just don’t let them score. And of course, the prevent defense that a game prevents is winning, right? And we see this in all sports. So what happens is when you see a team that starts to recognize their collective flow, that they’re losing it, you have to find a way for them to play aggressive, to lean in, to be in attack mode, right? The psychological opinion is that you have to give them something to attack. Interestingly enough, if you think about sort of the triggers for flow state, like the psychological triggers, they’re very primal.

Dr. Gio Valiante 45:40

It’s a very primal state. There’s a reason, for example, if you’ve ever seen like dog racing, there’s a reason they have those greyhounds chase a rabbit. Ever noticed that? They don’t just have dogs running around on a track. There’s always a rabbit and it’s always ahead of the dogs. Why? It gives them something to chase. You always know that in pursuit, runners run fast. That’s why you have people in marathon, hey, I want you to spot me. I want you to sort of pace me, right? Pace car or pace cyclist. As you’re chasing something, it triggers those primal psychological mechanisms that can lead to flow.

And so as a coach, you can scheme around it or you can do it with personnel, but your team always has to have something to attack. You can never let your team psychologically get on their back foot and go into protect mode. They start playing scared. They start making mistakes. They start hesitating. They start telegraphing what they’re going to do because that’s what fear does, right? Another characteristic of fear we talked about earlier is you start telegraphing because you’ve lost your confidence and the defense will prey on that. So as a coach, you have to find ways to either do it through personnel or scheme. Half-time is a really important time to reframe the game. But I know you guys are always coaching, hey, stay in attack mode. Stay aggressive, stay aggressive, penetrate. Oftentimes there’s a key player on a team that sets the tone for that in football. You could think of Ray Lewis. Ray Lewis lived in flow. He had so much energy and so much fight for the game. There was no chance while he was on the field that there was ever going to be any letdown of his defense. And he saw it, he’d call it out right away and those guys were on the bench. Bench is a very powerful motivator. And so oftentimes as a coach, there’s an NBA coach that I worked with. And I remember he said to me that he budgets a certain amount every year for a player who will never play meaningful minutes, but he’s so valuable to the locker room and to set the tone for the aggressiveness that the team needs. And so that’s what a smart coach does. He knows his personnel so well, hey, that’s my guy. He’s going to set that tone so that if that team is starting to fall, he’s going to be that spark, that trigger, that mechanism by which it’s going to elevate.

Dan 47:44

For sure. And when you talk about things to chase, like needing the rabbit in front of the dogs, all that kind of stuff.

For teams now, when you’re towards the bottom and you’re chasing better teams or when you’re in the middle and you’re chasing teams ahead of you, but high performing teams are often out in front with themselves undefeated or in first place or the best player in the world and how coaches can think about helping those teams, those players chase something when there’s not a lot of people or teams ahead of them but they’re still trying to elevate their performance.

Dr. Gio Valiante 48:13

I’ll go back to golf as an example. One of the most remarkable things that we’ve ever seen, really in the history of the game, is Tiger Woods was the only player in the history of game ever be able to do this. It was, he would start Sunday with a six-shot lead and then win by 12. He would extend the lead. What happens on a PGA Tour constantly is you’ll go into Sunday and you’ll see that there’s 10 players within two shots of the lead. And the leader will either hold on or fall back. And so the winner often comes from, right? Because now you’re playing with nothing to lose back against the one you could be fearless. Whereas the fear of losing the lead gets in these guys’ heads and they start playing scared and they overreact to the stakes, this is downward spiral. That never happened with Tiger.

And you’re like, how is he doing that? Because anyone who’s ever played golf knows playing with a lead, even Jack Nicklaus, the great Jack Nicklaus always said, I was always more dangerous chasing than I was with a lead. And Tiger, well, how does Tiger do it? Because Tiger wasn’t playing against the field. He was playing against history. He was playing against guys who had played 100 years ago. So yeah, I’m beating you guys by six, but you guys aren’t my competition. Ben Hogan’s my competition. Jack Nicklaus is my competition. And so Tiger was always playing the game against a benchmark that was higher than was around him.

You know, this is why, what do great coaches do? It’s like, hey, let’s not play the level of our competition. Let’s play the level of our capability. Steve Spurrier, former coach of the University of Florida football named Gators, was great at this. He was always talking about and coaching his teams to play against their capabilities. Some of the best games in, now you’re talking about 10 SEC championships in a row, in a national championship. Those teams would be scoring 40, 50, 60 points in a game in the fun and gun offense. But what coach would do is if he ever saw sloppiness or laziness or lack of commitment, didn’t matter if you were a superstar, didn’t matter if you were leading, you were out of the game.

Because he knew how dangerous that was because lack of motivation or sloppiness becomes contagious on a team, right? And so as a coach, there’s two responsibilities of coach. Number one, skill development, right? Make your player better, develop the skills. You don’t know how to do that. Number two is the constant framing and reframing. What is this about? What does this game mean? What are we playing for? And that’s a rolling, moving target. And one of the things I love watching elite coaches do is they’ll take a meaningless game and they will practice so hard that week. Because once laziness or sloppiness happens, it becomes a habit. And it’s like, hey, this is the most important game of your life, you don’t even know it. But then when it’s a huge game, well, that’s just another game.

Dr. Gio Valiante 50:45

You have to trust your training. Why are they doing that? It’s like when I coach players on the PTA Tour and they go to the Masters, the US Open. One of the things I’ve accomplished here is, hey, your seven iron flies as far as Augusta National does at your practice course. Like nothing changes.

What do we do there? Process, process, process, process. How does this translate to the NBA? There’s an NFL quarterback that I worked with who, this will speak to basketball, I think very clearly. What this player would do is whenever he was in a game against a marquee quarterback on the other team. So if he was playing against a Tom Brady or a Russell Wilson or a Patrick Mahomes or some elite quarterback, this quarterback would in his mind think, I have to play to the level of that quarterback. And he would start trying too hard. And he would start throwing balls into bad windows. He would start trying to force a win. He started making all these dumb mistakes, right? So think about that. If as a player, as a quarterback, you think your competition is the other team’s quarterback, now what’s the flaw in that? Number one, you’re never on the field at the same time as the other team’s quarterback. You can’t influence him. So what’s the right mindset of an NFL quarterback? Who is your competition? What’s two things? It’s the other team’s defensive coordinator and your playbook. You’re executing your playbook against that team’s defensive coordinator. There’s nothing to do with the other team’s quarterback.

What’s the equivalent in basketball? Who are you playing against? Is it score? Is it the opponent? Is it your own capabilities? Is it how well you played or how badly you played last week? Is like, what’s the exact right frame of mind for a given player or a given team in any given situation? Well, I think number one on the list always has to be, here are the plays we’re implementing in practice. If it’s a game that’s not against a superior team, it’s listen, we need to develop the habit of executing these plays because we’re going to be playing the NCAA tournament or the tournament at the end of the season. You have to develop the habits now, right?

So I want to see high level execution against these plays that we’re putting in. I need to see you play with speed. I need to see you be decisive. In other words, you’re framing and setting what this game is about. Even if it’s an equivalent function, oftentimes what I see great coaches do early in the season, not typically in tournament times, I don’t care if we win or lose this game. Here’s what I care about. Here’s why, yeah, here’s an example. I had a golfer last year who was in a three year slump, about to lose his card. It was like one of our last tournaments to play and he goes into Sunday with like a five shot lead. So he plays well on Sunday, all of his dreams come true. Secures his PGA to her card, makes a lot of money, validates the critics. Like there’s a lot at stake here. Here’s my conversation with him on Saturday night.

Dr. Gio Valiante 53:25

I said, listen to me, this is true in all sports. I said, I don’t care if you win tomorrow. Here’s why, if you win tomorrow, will you do it the wrong way? Like in other words, if you’re winning because you want to prove your critics wrong, you want to impress other people, or you’re doing it for the money, you’re doing it to get the monkey off your back. You may win, but you’ll never win again because those habits are in there. And for the rest of your career, you’re going to be playing scared.

However, if you go out tomorrow and you execute our game plan against the golf course and play your game and you lose, you’re going to win four times next year, but you can’t compromise. I’ve heard Lebron talk about this. I’ve heard Curry talk about Steph Curry. Steve Nash in his retirement speech articulated beautifully his relationship about playing the game for the sake of the game and against his capabilities. And so as a coach, if you can frame, hey, here’s what we’re playing for today, I need you to execute against this at a high level. And you own the framing of how to play the game. You’re developing the habits of taking ownership and you’re not externalizing your confidence. That’s a way to teach people to take ownership of their confidence.

And so as a coach, your two primary responsibilities are skill development and framing the purpose of that day’s practice, of that week’s practice, what you’re playing for, and how you’re going to measure success. Because you know as well as I do, if you win the game, but you’re developed bad habits, that doesn’t go well long-term. But if you lost the game and you played with discipline, you played with speed, you played decisive, you trusted each other, you played for each other, then you’re going to peak at the end of the year. And so there are times as a coach where you have to lose a game and tell your team, I’ve never been more proud. You guys have tomorrow off from practice. That was awesome. Or the opposite, you won a game and you throw a fit and you’re like, that was shit. You have to find a way to continue owning how you’re framing it for the team so they don’t get attached to results. They’re attached to the quality of the play. I always ask offers, what’d you shoot? You know, 72, good or bad 72. I don’t care about what you did and how you played. And if you’re playing at an increasingly high level, that predicts what we’re going to do long-term.

Dr. Gio Valiante 57:12

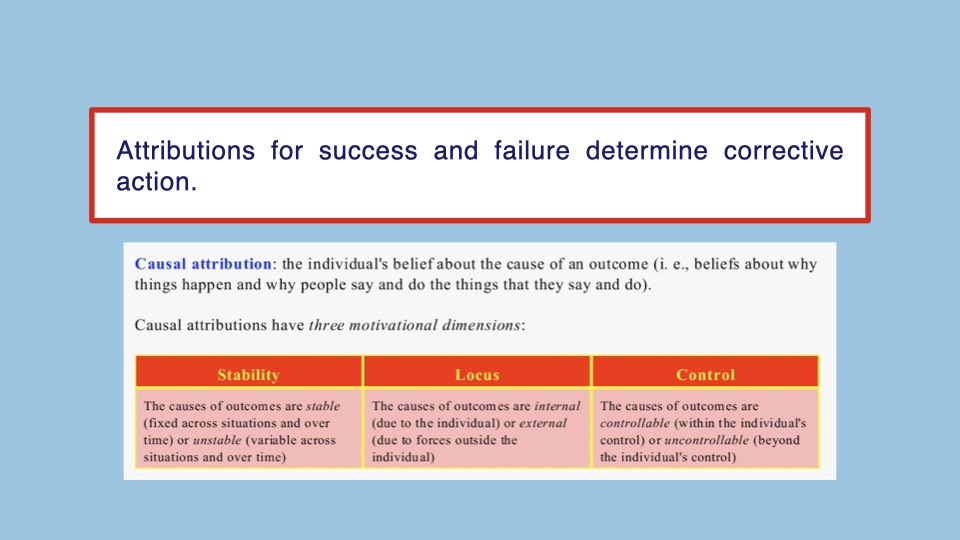

Every coach is in some capacity, in some way, a psychologist, right? And that’s why I get along with coaches. I’m a psychologist who does a little coaching, but these are coaches who are psychologists, and so we meet in the middle, we exchange ideas. So one of the most important questions for psychologists is this. You’re trying to recruit a player, you’re talking with your players, or you’re listening to players, and you’re trying to decide whether someone would be good or bad for the team. It’s some form of this. It’s to what do you attribute your success and said more simply, you’re playing well, why? Or hey, you’re not playing too well, why is that? What psychologists always look for is the word because. Once you hear the word because, or whether it’s implied, that’s when you need to start listening carefully.

Because what you often hear is a player saying, I’m playing well because I work really, really hard in the off-season to develop my skills and make sure my game’s at a peak level. Or you might hear a player say, I’m playing well because I’m better than everybody else. My talent, what I have you can’t teach. Or you might hear a player say, you know what, my teammates are making me look good. Or you know what, I’ve got great support in my organization, my ecosystem, my system, or the various things that players attribute success and failure to. Here’s why this is important. And this is actually worth points on the scoreboard. If you can understand this, and you can actually coach in a way, which a lot of coaches do this intuitively, but the psychology behind it is interesting. There are three bits of information in every because statement. It’s called stability, locus, and control.

Here’s what I mean. Stability. Stability is something that is changeable or not changeable. It’s either stable or unstable. Talent. If a player is attributing his success or failure to talent or lack of talent, you can’t affect talent. People basically believe that I have a given amount of talent. And the problem with that is if people are attributing their failure to talent, well, there’s nothing I can do to fix that. So they tend to give up and to check out. They get aged pretty quickly. Same with success. It’s a fixed thing. Conversely, if a player is attributing their success to hard work, that’s an unstable attribution. I can change my effort. Effort is not a stable. So stability, it’s either a stable feed factor or unstable.

Locus, it’s either internal or external. Going back to it, talent is something internal of me. It’s not external. My work ethic is something internal of me. It’s not external. If I start blaming coaches, that’s external. I blame my teammates, that’s external. I blame the media, that’s external. If I blame politics, that’s external. If I blame the price of it, so what you’ll see is the attributions players make going back to either talent or hard work, right? Stability is stable or unstable. Locus, is it of me or is it external to me?

And then control, is it something I can or can’t control? And every attribution that a human being makes can be fit on those three metrics.

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:00:09

Stability, locus, control. Think of a student in school, my kid comes home and he failed a quiz in ancient civilization. Hey, why’d you fail that? He’s like ah the teacher doesn’t like him, if the student believes his failure is a function of the fact that the teacher doesn’t like him.

Stable or unstable? That’s an unstable attribution, right? It’s like, teacher likes you or something could change. Locus, is it of me or of someone else? So if someone else, control, I can’t control that. And there are kids walking around by thinking that their success and failure is a function of how much they’re like. Or what he might do is say, you know what? For me to get better grades, I’ve got to get the teacher to like me. Now, what won’t he do is he won’t go study hard because he’s making the wrong attribution. Now, when you come to realize people make the wrong attributions 80% of the time, accurate attributions, you have to understand the design of the brain, assume that very few people work hard enough to make an accurate attribution. What you often see after breakups in college, now it’s like, yeah, what happened? I don’t know, he’s a jerk or all boys are immature. Like as a college professor, I hear this like, yeah, all boys are immature. So you had nothing to do with it. It’s out of use of an entire agenda. You’re externalizing your failures. What you’ll see oftentimes is when failure keeps happening, and they keep externalizing their failure. It’s never me, it’s always someone else. It’s always an externality. That’s a problem. Because what that means is you’re never going to take the responsibility to correct the behavior. So what you’re looking for, the most healthy attributions, then you always, what you want are accurate attributions. But the profile that you’re looking for is unstable, internal, controllable. You want players when they’re playing badly to say, it’s not working out right now, because some version of effort or something that’s of me that I can control, that’s not stable, that’s of me that I can control. What you don’t want is stable, external, uncontrollable. That’s when people give up.

just to sort of sharpen my own psychological toolbox. I’ll often read stories or headlines about teams that are in slumps. And one of the things that’s always interesting is when you see a coach blaming players, when you see players blaming other players. And the opposite’s true. What you see out of the great champions and great coaches is even when it’s not, you see it a lot of times out of team leaders, quarterbacks, NFL, point cards, the NBA, but leaders, it’s, hey, I gotta work harder, I’m not doing my job. Even when it’s other people on the team, what this former Navy SEAL, Jocko Willink, he’s got a book out, I think it’s called Radical Accountability or Extreme Ownership. What you see out of great coaches, great players is attributions that are unstable, internal control.

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:03:01

Here’s the beautiful thing, as a coach, if you’re a role model, I own this, you’re not playing it’s on me, I’ve gotta do a better job coaching. What happens early on, players will then, you’re right, coaches fall, then all of a sudden, they start taking after you, start teaching them, hey, take ownership of this, hey, if that guy’s not playing well and you’re a team captain, whose responsibility is it? You’re a junior, he’s a freshman, his bad play, is that his responsibility or your responsibility? And if you’re not gonna take responsibility for that, I’m gonna find someone who will, because great players also take responsibility for other players succeeding.

One of the questions, and this is a really powerful question, I’ll often do with corporations, if they’re having a bad quarter or a bad year, what I’ll do is I’ll go in the day before and people always wanna pull me aside and say, hey, it’s that guy’s fault or this guy’s fault, they’re only playing, it’s her, it’s it. Everyone sees what they believe to be the cause of failure. But when things are successful, this is what’s called the attributional error, when things are successful, human beings take a disproportionate amount of credit, when there’s a lot of failure, they externalize, it’s never them. So what I’ll do, when teams or organizations are not performing well, start with a simple question, I sit everyone around the table, I say, I want you to write a question down, what part of the problem am I? And so if you’re a salesperson, an organization, even if you’re the number one performer, and three other people on team are bringing results down, the first thing you think is, I’m not the problem, I’m posting numbers, like, oh, really? Okay, have you taken time, you see the mistakes they’re making, have you taken time to help them? Are you coaching them? Are you sharing information with them? In other words, very seldom, if you’re part of an organization, and if it’s not performing, people by human nature are, oh, hey, I’m doing my job, not my fault. Okay, what part of the problem am I? You really start doing the work on it. If you’re gonna take credit for the success, then you better sort of balance the ledger and understand that if an organization or team is not failing, and you ask that question, almost every single time, there’s an answer where you can help other people, and then all of a sudden you elevate people.

Dan 01:05:06

Dr. Gio, trying to relate some of the things we talked about earlier, the fear and anxiety with what we’re talking about now.

Is there any relationship between high performers that have internal versus external locus and fear? What I’m asking is, did the better performers say internally, take things on themselves so that when they know how to work on things so that fear doesn’t drive them in a negative direction versus those that are external driving in a bad direction?

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:05:33

You have a job as a professor, Dan. We do these studies. So what you’ll find is there is a statistically significant relationship between internal controllable attributions, confidence, inversely related to fear, and positively related to flow states. So it’s all four things we talk about travel together.

Now, why is this? When do we lose confidence? Well, we lose confidence when we feel like we have no control over outcomes that are important to us. Confidence is directly related to controllable factors. When we have belief that we can somehow influence the course of our lives, if you look at, for example, kids who have been through a really hard time during any sort of trauma that happens in childhood, the reason that those people tend to be anxious in life, no matter how rich they are, no matter how successful they are, is because they learned very young that bad things happen to me over which I have no control. The world happens to me. So what do you do psychologically? Oftentimes, if you reframe it for people, it’s, I don’t know, you’re not a victim, you’re a survivor. And just that one reframing is, look how strong you are, look what you were able to survive. And all of a sudden, look at how you control the fact that they got, and you give people some sense of ownership over their path in life, then they start to believe that, then they start to manifest it.

So to your point, controllable attributions, build confidence, increase work ethic, increase skill. And by the way, what you want is confidence and competence that go hand in hand. You don’t want fake confidence. You don’t want people walking around believing they’re great when they’re not. What do you want? People having their confidence rooted in their skills. What is skill rooted in? Work ethic. What’s work ethic rooted in? Control. And so what you see is that the causal chain that ends with confidence starts with the belief of, I control my own destiny. What you’ll see is a lot of these people manifest their excellence because their belief in, hey, I’m as good as I’m willing to work hard. I actually have a lot of control over where I end up here and where this team ends up. And to the degree that everyone can take accountability. And it doesn’t always have to be on the floor. It’s, you know what? I’m doing things in the locker room. I’m doing things around the facility. I’m doing things to be a locker room guy. I’m taking responsibility, even if it’s a small thing. We have these people in organizations, I’ll often recommend people say, should I hire this person or not? Like hire that person. Culture carrier, we’ll call a Swiss army knife, right? You’ll do whatever it takes to make the organization better.

Because Swiss army knife, you do a lot of different things with that person. If you can find a person, you’re in schools, by the way, you knew who that often is. Sometimes it’s the secretary. Sometimes it’s the person greeting the kids of the day. Sometimes it’s like what we think is the most insignificant role.

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:08:15

People in the mail are often the most important culture carriers, which leads to success. And when you talk to these people and interview these people, which we do in psychology, we realize they have real ownership in the success because they take pride in what’s happening around them, independent of their salary. And so break it down, make an internal controllable attributions where they’re responsible for other people’s success, elevates confidence, increases the probability of flow and decreases anxiety. That’s the causal chain.

That’s the psychological profile. So as a coach in a nutshell, you’re always trying to find the balance. A little bit of overconfidence elevates skill because it leads to risk taking, it leads to creativity. You learn from mistakes, but you don’t get defined by them. Too much overconfidence is bad. Let me tell you what a killer means. Skill here, confidence here, all of a sudden skills find a way down to the confidence level. So in as much as you’re trying to create accountability, you always have to have a team believing that they’re capable of more than they’re doing. The profile for excellence psychologically is confidence is a little higher than skill. You have to believe you’re capable of more than other people believe you’re capable of. You’re taking ownership and victory and defeat. You’re being fearless. How do you be fearless? You allow people to make mistakes without beating them up for it. In fact, sometimes you encourage, hey, that was a great risk you took. Keep shooting. Don’t give up. Keep trying. That’s going to work eventually. You’re building the confidence in the risk taking culture. Hey, trust your teammates and you’re teaching teammates not to beat each other up so that everyone’s taking risks to get to hold each other accountable.

Pat 01:09:47

You mentioned, too, at the very beginning of our conversation that it’s much easier to lose confidence than it is to gain it. And so when you go through the chain that you went through that leads to confidence, if all things are being the same in your work ethic, you know, as a coach, like, hey, we’re still training the same or the player, I’m still working hard. Where seems to be the kink in the chain that leads to a player or a team losing confidence?

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:10:12

Here’s the catchphrase. The pain of failure hurts more than success feels good. So I just want you to think about that.

The pain of failure hurts more than success feels good. Now, why is that? So what happens is, when you fail, and you’re inclined to sort of be hard on yourself, like beat yourself up the kind of person who’s sort of hard on himself, or other people are hard on you, the brain uses adrenaline, right? So all memories are not created equal, by the way. So a painful memory, the brain uses adrenaline, and it highlights that memory in the neural network, almost like a yellow highlighter, and it says, hey, remember this. So you don’t do it again. So there’s already a bias toward remembering failure more than success. As time passes, even if we succeed more than we fail, we remember the failures more.

So in our memory, failures elevate. And that’s why everyone can remember, over the first time they were embarrassed in middle school, or the first heartbreak they had, or the first time they felt in danger or fear, because the brain is legitimately highlighting that memory. Now, here’s what happens from there. Confidence is built on four pillars. There’s four types of experience that build confidence. Number one is just direct experience, the success and failure. But remember, we remember failure more over the course of a period of time than success. So what can you do as a coach? Put together highlight reels for your players, for the love of the Lord.

Let them watch themselves being successful. Why? You have to find a way to counteract the pain of failure. The world is so punishing a failure, particularly in the public eye, you have to find a way in that moment when the brain says, what do I do in this moment? It goes back to success. You have to work at that. Otherwise the failures accumulate, particularly if the player chokes. If a player chokes, and then spends all night thinking about it, and then looks at all that’s happening at that point, is the brain is saturating that memory in adrenaline. And it’s a chemical thing where it deepens that memory. And all of a sudden that same situation, the brain’s likely to go back there, likely it’ll play a scare. So we were all designed for underperformance because we’re all designed for underconfidence. That’s number one. The second source of confidence, how verbal and social persuasive things people say to us. It’s called a double-edged sword. If you’re gonna get your confidence from other people’s compliments, you’re also liable to lose confidence in their criticism. So we tend to try to teach players, hey, don’t listen rather than people say, a few people, your family, who love you, your coaches, but in that you can’t get your confidence by the medium. But that’s a source of confidence. The things people say matter. Third one, called vicarious experiences. Think of it this way. If the three of us go for a math test, we sit down together, we sit in class, and like, hey, do you guys study for the test?

Dr. Gio Valiante 01:12:55

And Dan’s like, oh yeah, I’ve been studying for all week. And Pat’s like, you have a test? Yeah, it’s a huge test. And you’re like, holy cow, I didn’t even know. So we all take the test. Go to class the next day, and all of a sudden, I made a B, Dan makes a C, and Pat makes an A. Sounds familiar. Pat didn’t study, but he made the A. Dan and I worked our families off. We made Bs and Cs.

What is that gonna do to our confidence? It’s gonna lower it. Because we often gain or lose confidence relative to what we see other people do, called vicarious learning. So really what’s happening in that dynamic is a player’s looking at another player, and they’re saying, you know what? I can never be that good. And so all of a sudden, it diminishes your confidence. So what you’re trying to do for every individual is show them a path to where they can be the best version of themselves. Because what we know is that everyone peaks at different ages to inform your confidence relative only to what someone else is doing is a fool’s game. It’s external to you, it’s not controllable, and it’s stable. I feel like that person’s just better than me. Stable, external, uncontrollable. That limits motivation, it limits learning, and literally at a mechanistic, psychological level, you’re putting a ceiling on your ability.